Normal as a Political Weapon: On Queer Assimilation and Pride Season

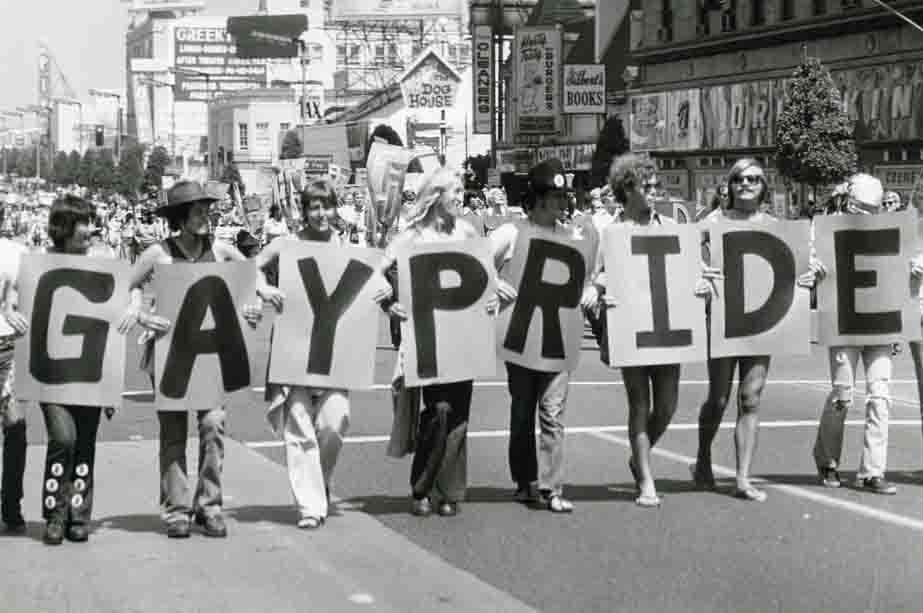

PHOTO: LIZZY JOHNSTON

On the surface, Pride looks like one big queer party: rainbow floats, glitter-covered city streets, disco balls, gold lamè bodysuits, and enough liquor to leave most of us strung-out well past the Fourth of July. But, really, Pride is more than a drunken celebration of queer voices, bodies, and lives; it also commemorates the anniversary of the Stonewall Rebellion, the riot that acted as a catalyst for a nation-wide gay liberation movement. Pride month, then, is as much about celebrating as it is about reflecting on what “gay liberation” means to queer people today.

More than a moment to be memorialized, “liberation” implies an ongoing political battle, enmeshed with various other struggles, among them: the struggle for black lives; the modern women’s movements, movements against capitalism, poverty, and imperialism; and movements for transgender visibility. Queer (as opposed to “gay”) liberation is complex and multi-faceted. The numbers of people, politics, and identities that fall under the modern LGBTQ+ umbrella inevitably clash and battle with one another, especially during Pride month—a time when queers from drastically different backgrounds protest, dance, drink, and throw glitter bombs together.

"A large contingency of the LGBTQ community has no pressing desire to challenge convention: they want privately owned homes, well-paying jobs, monogamous marriages, successful children, and the respect of the majority."

One of the most hotly contested parts of Pride season is the debate about the gradual mainstreaming of Pride festivals and, by extension, certain queer identities. As Pride grows, it is becoming increasingly corporatized—multi-million-dollar companies like Target and General Mills are rolling out specialty products for queer consumers who want to wear, sip, and eat Pride the Brand. And police, long antagonistic and violent towards queer communities (particularly queer communities of color), now walk alongside Pride participants in many major Pride events. As a result, the radical, anti-establishment tactics that fueled the Stonewall Riots and many other gay liberation protests have been sanitized by the light-hearted, expensive festivities that make up Pride today. But many attendants don’t so much mind Pride’s mainstream appeal. According to some, the freedom to conform is a form of liberation.

In liberal politics, most discourse surrounding “LGBTQ+ rights” focuses on the rights of queer people to assimilate into existing sexual and social schemas and be seen as “equal” to most heterosexual people. Gay marriage rights, rhetoric that claims sexuality and gender identity are primarily biological/fixed, and the corporatization and sanitation of Pride all speak to queer people and movements that desire to fit within the status quo. Assimilationists, as some theorists have called proponents of queer assimilation, might desire for straight friends, family members, and the state at large to see their identities as fundamentally similar to the identities of heterosexual people. To them, being queer isn’t necessarily a political imperative or a conscious act of dissent, it’s incidental—a part of their humanness. And why not? A large contingency of the LGBTQ community has no pressing desire to challenge convention: they want privately owned homes, well-paying jobs, monogamous marriages, successful children, and the respect of the majority. Considering the major victories assimilationists have won politically and culturally, living a “normal” life while queer is possible for more and more of us. And since being labeled as “deviant” confers crushing disadvantages, becoming “normal” is more than enticing.

"We who have the most clout in straight society share a political imperative to stand with those queers who have the least. "

But what of the queers who can’t—or don’t want to—assimilate? There are those of us who believe that “queer liberation” necessarily means freedom from all axes of oppression, which also means standing in solidarity with the people most “othered” by society and the state against the institutions that have marginalized them. This could mean advocating against police at Pride because of the way police have brutalized black and brown people and censured queer expressions of sexuality and gender, even if their presence makes some attendees feel safer. It could also mean critiquing (or rejecting) marriage and monogamy because of the way those institutions have perpetuated misogyny and heterosexism in society broadly, even though queer people might personally enjoy being married or monogamous. Essentially, arguments against assimilation are rooted in the belief that institutions that are fundamentally oppressive and exclusionary cannot be adequately reformed. Queer anti-assimilationists seek alternatives to existing norms; specifically, alternatives that challenge heteronormativity and the prescriptive moral and ethical codes that are enforced on society from the top down. They recognize that conformity is a social construction and make the point that it is also a political weapon. Sure enough, as Pride celebrations become more mainstream and “gay rights” make legal headway, some members of the community do fear losing their elevated status via contamination with less “normal” queers.

For instance, in a CNN comment thread about a transgender father who gave birth to a child, one commenter who self-identified as a gay man called the father’s experience “unnatural” and blamed gender-nonconforming trans people for the prevailing belief that the queer community is mentally ill (his insults were then “liked” by dozens of other commentators). Of course, just a few decades ago homosexuality was widely considered to be a mental illness and gay parenthood was deemed “unnatural” or outright criminal. As this rhetoric has changed or, more aptly, adjusted to new targets, some of the very people who once had cause to rally against it are internalizing it and projecting it back outward. In the above example, the relative amount of “normalcy” the gay male commentator has achieved possibly entitles him to join in on the policing and gaslighting of queer people who still challenge norms about gender and sex. This entitlement is a political problem. Though the LGBTQ+ community is more visibly diverse than ever before, its most marginalized and least marginalized members lack political solidarity, leaving a great deal of queer people feeling underserved and unwanted by the public-face of the liberation movement.

VIA "NO PRIDE IN POLICE' FACEBOOK PAGE

If you ask me, corporatized Pride celebrations that cater mostly to the primarily white, cisgender, and middle class gay men and women who have led the “queer assimilation” front in liberal politics are a far cry from queer liberation. However, even as a critic of assimilation, I sympathize with people who genuinely want the right to be apart of experiences and institutions that long excluded them. As I said before, being labeled “deviant” has crushing disadvantages: rejection from friends and family, increased vulnerability to violence, discrimination in jobs and housing, etc. Assimilating is easier, and safer too. But some queer people—particularly gender-nonconforming and trans people of color—do not have an easy path towards assimilation. Their identities are often, in and of themselves, a blunt challenge to heteronormativity, white supremacy, and cissexism. And their welfare is not being addressed by liberal politics. That is why even those of us who personally desire the trappings of “normalcy” must still be willing to stand against prescriptive moral and ethical codes that deem some expressions of queerness acceptable or “normal” while villainizing others. We who have the most clout in straight society share a political imperative to stand with those queers who have the least. If we believe that Pride is as much about liberation as it is about celebration, we must recognize that conditional acceptance is not enough, especially when it is granted at the expense of queer people who have been continually excluded from mainstream. Though it is not necessary or possible for us all to want the same things, our collective liberation requires a collective recognition that the right to “stand out” is even more essential than the right to “fit in.”

----

RM Barton is a writer and activist living in Roanoke, Virginia. Originally from Maryland, she moved to Southwest Virginia for school some five years ago, and has since become invested in queering southern space. She is the co-lead of The Southwest Virginia LGBTQ History Project and the publisher of The Southwest Virginia LGBTQ History Project Zine, which aims to illuminate queer history through queer art and storytelling. She blogs at rmbartonblog.wordpress.com

Archive

- September 2025

- August 2025

- May 2025

- February 2025

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- October 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- June 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015