The Resurgence of Gregg Araki’s Teen Apocalypse Trilogy in the COVID-19 era

“I feel like a gerbil smothering in Richard Gere’s butthole.” Jordan White states somewhat nonchalantly in The Doom Generation, and honestly, more often than not, same.

The year 2020 (still heavy on our hearts and holes) was an infinitely fluctuating mobius strip, lasting for both mere seconds and countless centuries, depending on your current mood and/or level of horniness and/or commitment to “unpacking.”

Mass hysteria was a common side effect of institutional failure. Altered perceptions of reality are a widely reported symptom of cabin fever. Sensory deprivation was a direct result of the monotonous slurry of zoom conferences many of us were subjected to. As a longtime service industry worker (bartender at a queer venue) the sudden lack of tactile engagement left me thoroughly high and dry.

While first learning how to navigate this abject temporal vacuum, there were several stumbling blocks I encountered on my own path to equilibrium; prolonged melancholy masturbational odyssies, followed immediately by sharp pangs of Saggitarian wanderlust. Late night interpretive dancing or harmonizing with the radiator could only take me so far. How I longed to cruise the open highways and crowded bathhouses in search of unbridled gay whimsy yet again.

Before isolation, queer folks already had a nuanced and singular relationship to the concept of time (a phenomenon that my platonic amorous throuple affectionately refers to as “Gay Delay”) which was inevitably complicated by the cruel bureaucracies of contagion:

*forced separations from chosen family.

*state-mandated immobility.

*barely disguised (read: blatant) housing discrimination.

*perpetual risk of infection.

*the reemergence (commodification) of hygiene theater for capitalist gain.

*the fatalistic implications of bodily autonomy.

While false equivalencies have certainly been made between COVID-19 and the HIV/AIDS epidemic, there are certain parallels that were unavoidable in the cultural consciousness. Oblivion is not only mass-produced and televised, but also swept under the rug and just beyond your bedroom door.

The banality of oblivion is perhaps one of the many reasons why the “Teen Apocalypse Trilogy” by New Queer Cinema pioneer Gregg Araki has received a resurgence in popularity throughout the pandemic.

Araki, arguably the spiritual godfather of bisexual lighting, the Patron Saint of West Coast Fag Nihilism, made three distinctly Californian contributions to cinema: Totally Fucked Up (1993) The Doom Generation (1995) and Nowhere (1997) each a stylized exploration of queer teenage malaise and eroticism amidst the futility of the nineties cultural wasteland.

I had the pleasure of revisiting these films during quarantine via This Light, a communal online media archive created by the artist Andrew Norman Wilson, a project that “emerged out of a desire to make private viewing habits public, as common space continued to dissolve into private property, and our attention was pulled towards the monetized distraction of streaming content in solitude.” This Light, at the height of ubiquitous panic and turmoil, was an invaluable resource for emotional decompression and a cloistered cinephile’s wet dream.

The Doom Generation in particular was a formative film for me in my senior year of high school, when I brazenly began to identify as a “wayward pansexuale.” Watching it again, while basking in the virtual presence of my queer companions in a time of unprecedented generational crisis, was unexpectedly cathartic.

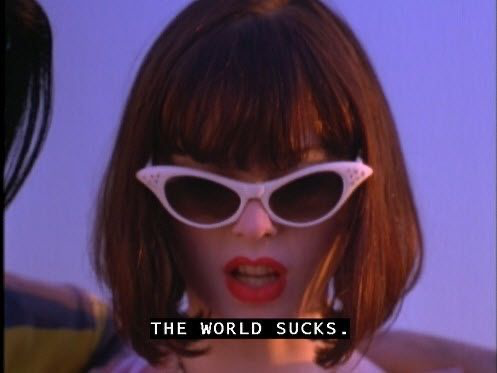

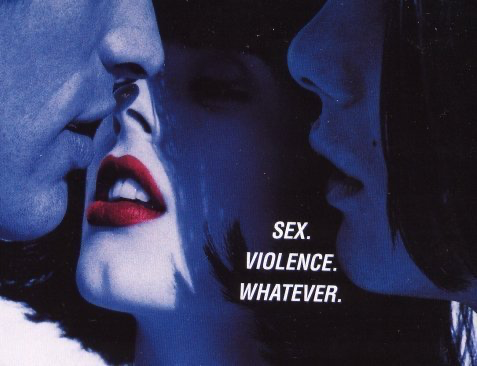

The Doom Generation (infamously promoted as “A Heterosexual Movie By Gregg Araki,” perhaps to troll the stodgy and easily flummoxed film critics of the time) follows a bizarre fuck triangle between casually callous Valley femme fatale Amy Blue (Rose McGowan in an immaculate black bob) her timid and good-natured boyfriend Jordan White (the effortlessly dreamy Araki mainstay James Duval) and amoral interloper Xavier Red (the carnally unhinged Johnathan Schaech). This hapless teenage trio is marked by incidental violence, satanic numerology, and multiple cases of mistaken identity as they take to the open road to flee persecution, with armageddon lingering lackadaisically on the horizon.

The morose glamor of aimlessness, of neon-streaked hormonal entropy, is intrinsic to the film’s design, as is Araki’s signature incorporation of shoegaze music, featuring such bands as Cocteau Twinks (ahem, Twins*) and a particularly memorable usage of Slowdive during a breathless finale sequence. The endless desert highways navigated by these sexually inquisitive flaneurs provide a purgatorial backdrop for the growing pains of fluidity. The emphasis on transience, both erotically and geographically, serves as a pointed critique for the often hostile trappings of heteronormative domesticity. It was all too easy to seek refuge in this romanticized and wistful wandering while confined to our apartments or stuck in our parents basements, anxiously awaiting the distant promise of a vaccine from a rapidly eroding administration.

Both The Doom Generation and the final film in the Teen Apocalypse Trilogy, Nowhere, explore the complications of queer polyamory while suffused in a pervasive yet playful ambience of existential dread. James Duval is once again front and center as moody sweetheart Dark Smith, who is conflicted about his non-monogamous relationship with Mel (a savvy and ephemeral Rachel True). This time the apocalypse is rendered as candy-colored extraterrestrial invasion, the encroaching fear of the adolescent unknown. Described as “90210 on acid” at the time of its release, Nowhere presents to a modern audience a queer nostalgia that is both prescient yet inaccessible, with an ensemble cast of chic and sexually ambiguous Los Angelites in multiple sensuous configurations. It was a vicarious thrill to see these chaotic arrangements unfold while actively challenged to negotiate new modes of intimacy in the depths of gay cyberspace.

For many of those made involuntarily celibate under the strictures of quarantine, Araki’s cinema invoked the beguiling messiness of modern queer polyamory, in all its myriad aches and dizzying splendors. Viewers took solace in the kinetic physicality of these angst-ridden lovers, and derived remote pleasure from their tempestuous infatuations. These films made the queers yearn for all the sparkling intricacies of entanglement, and actively crave the logistical pathos of not only fisting your therapists’ partner at the sex club, but then processing the encounter with them over lavender oat milk lattes the morning after.

“It's like we all know way down in our souls that our generation is going to witness the end of everything. You can see it in our eyes. It's in mine, look. I'm doomed. I'm only 18-years-old and I'm totally doomed.” Dark scrawls in his diary, a sentiment that is truly timeless, irrespective of age or subjective cataclysm.

We all need the highly stylized drama of personal catastrophe, every now and then.

—

Kamikaze Jones is a writer, interdisciplinary artist, and amateur porn detective currently based in Connecticut.

Follow him on Instagram @kamikazejones_

Archive

- February 2025

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- October 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- June 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015