Portrait photographer Michael James O’Brien captures Queer icons, artists, and moments in time

PHOTO BY ZOLTAN GERLICZKI // PORTRAIT BY ERVIN A. JOHNSON

The full version of this interview appeared in WUSSY vol.07 printed edition.

That issue is currently sold out / out of print.

A photograph freezes a subject in time. It arrests movement and change. It makes a fleeting moment permanent.

But strangely, the elusive, entwined themes of loss and transformation always seem to predominate in the images of Atlanta photographer Michael James O’Brien. Whether he’s photographing drag artists, celebrities, young men, artists, models, writers, activists, or even still lifes, the notion of mutability, of an irretrievable past, of a former and impermanent self that has been willed into the present, is always foremost.

It’s not surprising then to learn that O’Brien worked as a photographer during a time of great change and loss. “A friend of mine and I were walking to take a class at the New School, Greek or something like that,” he says. “We saw a sign for ACT Up’s first meeting and we both said, ‘You know what? I don’t think we need to take Greek lessons right now. We need to do something else.’ That’s when we started going to those meetings. There were eight of us around a table.”

Wussy sat down with the photographer, activist, poet, and teacher, now a professor at Savannah College of Art and Design in Atlanta, to discuss his life in art, words, and activism.

I was interested to learn you studied with the great 20th-century photographer Walker Evans. Can you tell me about that?

Even though he’s legendary, I have to say, at the time I was very casual about it. I liked him, I understood the work and I thought of the work as great. But at that moment in the 1970s, photography wasn’t what it became. He had his first show at MOMA when I was still studying with him. We were still on the trajectory of photography becoming an art form.

I’d come from having majored in English and political science at Yale. I realized really quickly I wasn’t going into the state department which is what everyone in my generation wanted to do. I quickly reorganizaed myself and applied to art school. I liked photography because you could be in the world. You have to be out there or else there’s nothing in front of the camera. It was a combination of something literate and phenomenological.

I only had enough stuff to apply to Yale because I was at the deadline, and I could just walk over and drop off my things. I did get in. I was only the student in photography. When I started, it wasn’t a discipline in grad school. It was “Fine Arts.”

Walker kind of pulled me in. Working with him was amazing because he was at a point in his career where he didn’t have to teach. He just sort of mentored. With him, it was about content. I was the only one in the class. We would meet in an office somewhere, and we’d talk about a lot of stuff because I’d been an English major, and I kept wondering if I’d made a mistake. We’d talk about French literature or any other topic other than photography. At some point, he would zero in about work I’d brought in. He didn’t expect you to do what he did. He didn’t only teach documentary photography. He was fantastic, and the things everyone says he said, he said, like ‘Color is vulgar.’ I never took a color picture in three years. Everything was medium-format or large-format, which I still do. He had a thing about clarity and resolution. I didn’t realize some of the things I’d learned til years later because I moved to New York right after school.

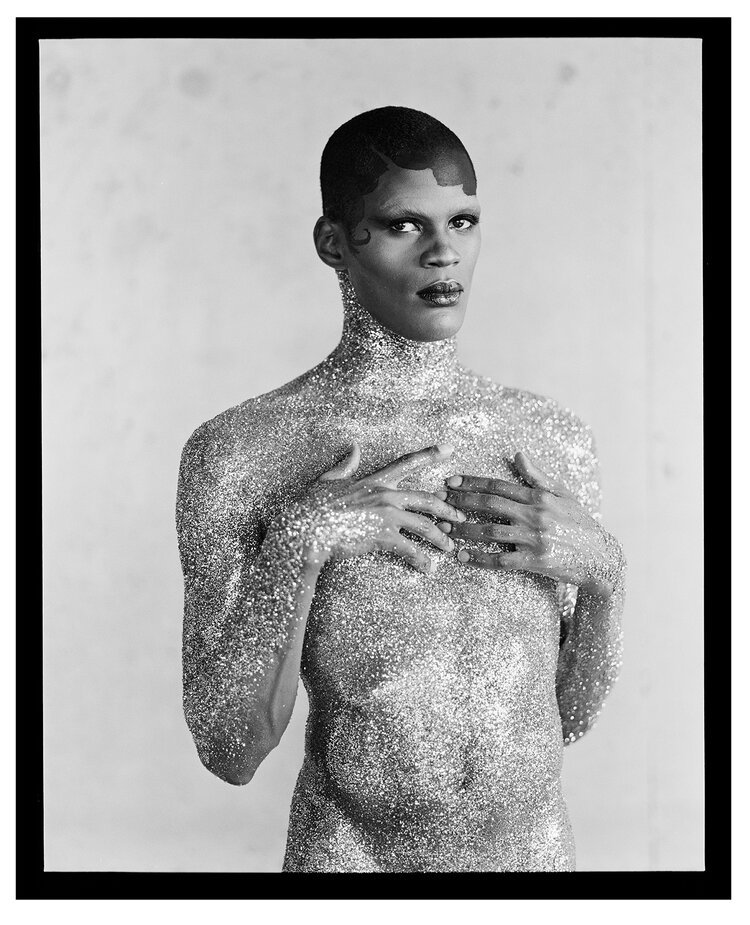

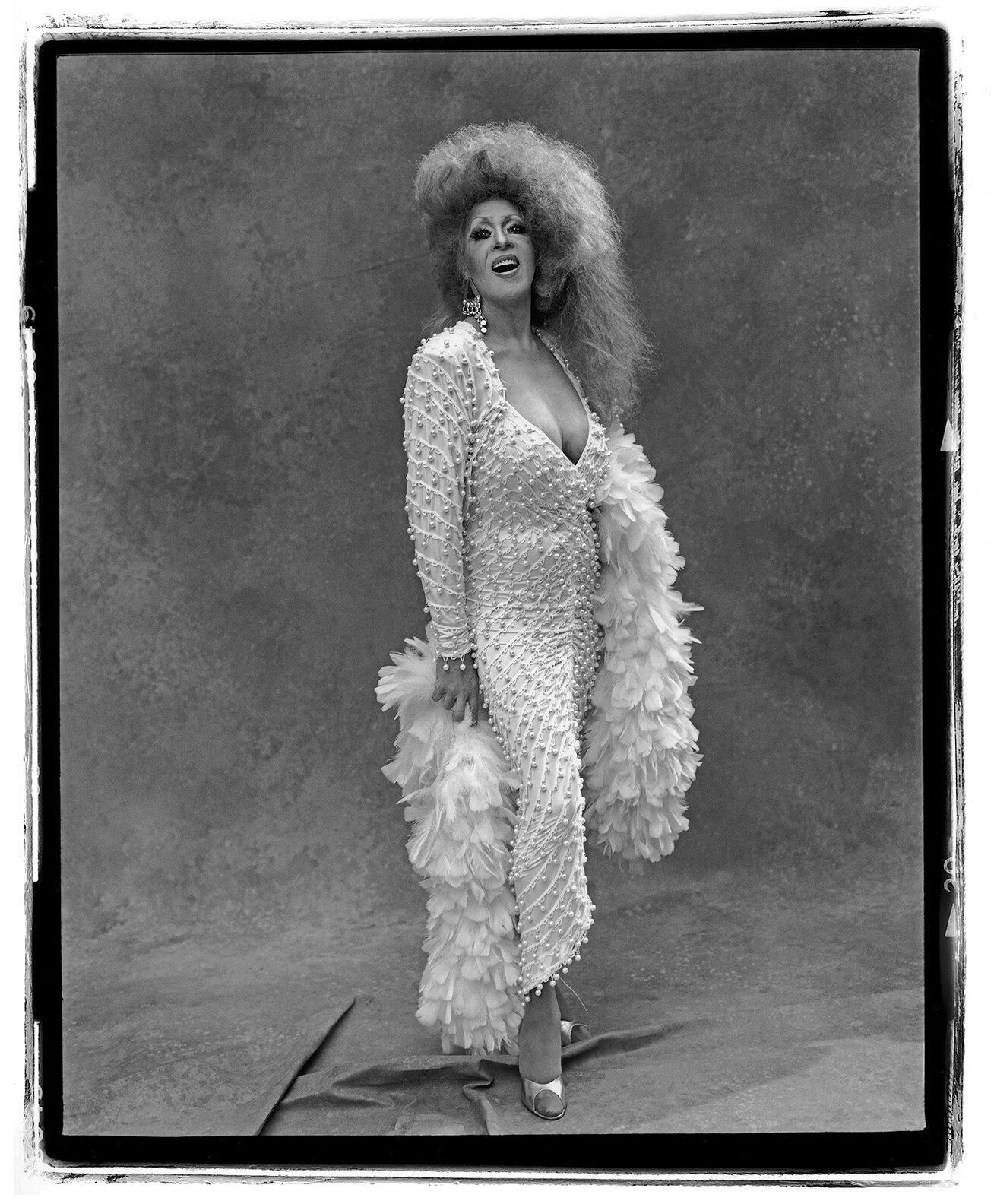

O, DORIAN (DORIAN COREY), WIGSTOCK, NYC 1992

Your primary subjects are people. What interests you about taking a portrait? How does a portrait happen for you?

I think it started from the beginning. First of all, I’m not interested in photographing nature. I don’t like Ansel Adams pictures. There was a hilarious time when Ansel came to New Haven, and Walker asked me to drive him around. It was exactly as you would imagine, him leaning out the window like he’d never been to a city before, waving his cowboy hat at people. He met with four or five students at a table, Walker at one end in a tweed suit, Ansel at the other looking like he just got off a plane from Wyoming. The students were busy being so excited about those nature pictures of the mountains and all that stuff. At one point, we were talking about what photography can do, and Walker said “Oh, Ansel, I will always feel that the true subject of photog is the hand of man.” That for me, that was it. For me, I only wanted to do things that indicated humans. A camera is a machine. We made it. We’re out there doing stuff.

The other huge thing that directed me: I was in Paris when Bressai died. I remember the headline in a bookstone: “The eyes of Bressai are closed forever.” Even before he died, Bressai’s pictures were the pictures that made me want to take pictures of people: the pictures in the Bal Masqué, the pictures in the bordellos, the pictures of the gay balls.

I think part of it is you have to balance how much time you spend alone and how much time you spend in the world. I just felt like for me the contact with people was terribly important. The trick for me was portraiture to move away from being just a picture that showed what someone looked like. It’s not just an idea of how someone looks or about making them look better.

You photographed a lot of the stars, artists and famous drag performers who rose to prominence in the ‘80s and ‘90s underground New York scene.

They weren’t all famous people by any stretch of the imagination. They could be guys I saw on the street. At that point, the early 1980s, nightclubs ruled New York. Everything was about nightclubs. Everything. The Mudd Club. Dancetera. Jackie 60. New York was smaller then. People had to go out if they wanted to meet someone. They couldn’t do it on Grindr, and they didn’t do it on Instagram or Facebook. They had to go out. Every single night you went out. There was no question about it.

I never did drugs so I was aware every time I was going out, thinking about it, how it affected culture, how it filtered up and down. The AIDS crisis had started so we were starting that crossover between wild nighttime abandon and political reality. I thought: here’s an intersection between activism and nightlife. Drag queens seemed to be at the center of that. It’s kind of a capsule, a kind of history ... I did the last pictures of Dorian Corey before she went into the hospital with AIDS. I photographed people at Wigstock. I took a huge gray canvas and two friends of mine helped me get people on it. I love doing all that.

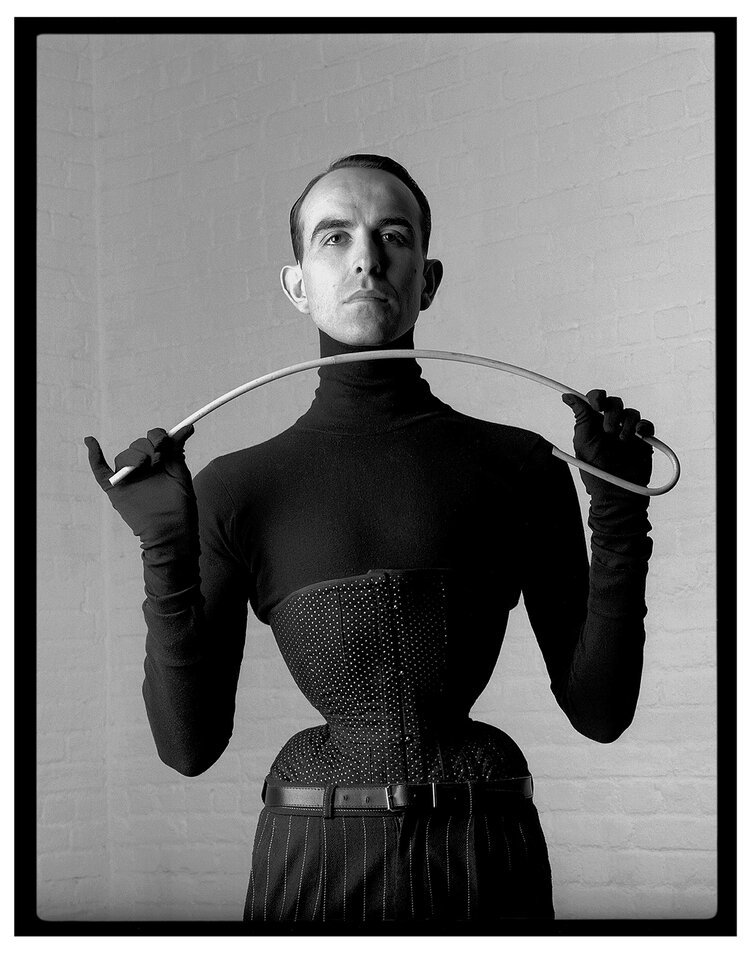

It’s an ongoing body of work because drag has changed. At that point, it had a whole ‘in-your-face’ political dimension, and the people I photographed weren’t female impersonators. I was doing deconstructed, crazy, political drag about that moment we lived in. Even when I photographed someone like Quentin Crisp or Allen Ginsburg or Jude Law, all my work--whether I was commissioned or found someone to photograph--has always been about perceptions of gender. Always. How someone dealt with that in the world that we all grow up in. If it was Jude Law, there was a feminine side. It wasn’t about some macho nightmare. Hopefully we’ve had the last straw of that.

Many of your subjects are famous, but in your Portrait of a Young Man series, the subjects are basically anonymous young men.

I cut down to the basics, because I was overwhelmed with everyone else’s vision. I wanted to work with no stylists, no hair, no make-up, no assistant. Nothing.

I started in 2000. You’d see these Valesquez or El Greco portraits called “Portrait of a Young Man.” You don’t even know who the young man is. There’s a mystery behind it. I thought: What if I did a portrait of someone and I didn’t know is that person was a drug addict or a writer or a waiter or whatever. What would it mean to have portraiture like those pictures? I’m fascinated that I have to approach this picture as a portrait of someone and interact with them without having any of the backstory … I’d be in a nightclub or on the street, and I’d see these young men, but I didn’t know them. I didn’t have a story. I’d get a phone number and set up a one-hour timeline. Everyone had to come in black with a little white, no logos, no bright fashion, nothing. I narrowed it down to one pose, so they would become typologies. I’ve done them in many cities, including Atlanta. I’ll stop when I know it’s time to stop.

Are there any famous subjects you’d like to photograph that you haven’t gotten the chance to yet?

The people I want to photograph are probably impossible. In the 80s and 90s, I could photograph someone like Jude Law. Nobody came to the studio. It was in my apartment. That was it. In the picture that was published, he was wearing a jacket of mine we liked better than the one he brought. That was another world. When I photographed Keanu Reeves, I went with him alone on his motorcycle to El Matador Beach. Within a year of that, you could no more photograph a famous person than fly to the moon. Seven people come. This person’s job is to stop you from doing this. That one doesn’t like the dress. That one doesn’t like the food. I stopped photographing famous people intentionally. I don’t want any part of that.

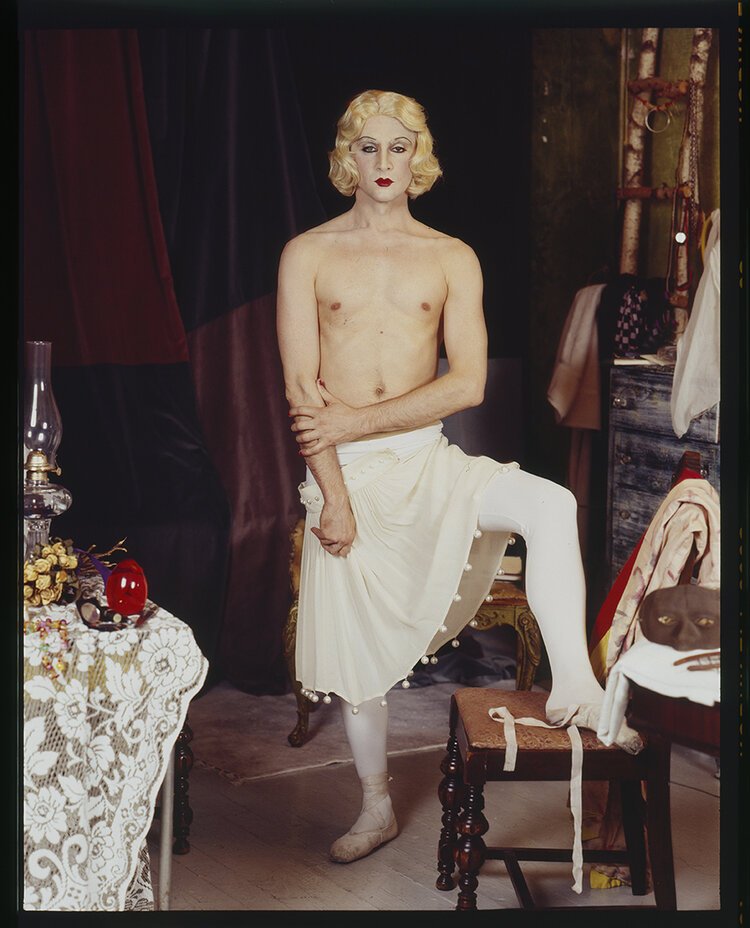

STILL LIFE WITH LEIGH BOWERY’S BUTTERFLY, PARIS 2003

The title of your series “Paris Interiors” sounds like something from Architectural Digest, but the images themselves are something else entirely. They’re somewhat sinister, haunting images of empty sex clubs.

I did that on purpose because i’d been doing things for Architectural Digest. I stopped. I did that series when I didn’t have to photograph Ralph Lauren sheets on somebody’s bed. I was in Paris, and I thought about the energy that exists in those places when they’re empty. I didn’t want to photograph people in them, and even if I had, I probably wouldn’t have been able to… It’s a little bit like when being gay didn’t mean you could get married and get a mortgage. I have no problem with that, but it never was my fantasy. In a way, I like having a sinister quality of having to go to weird part of town, people love to dress up in those situations. I like the idea of uniform. I liked the idea of dress code and uniformity. I think people like walking down Rue Charlot in full head to toe leather drag, slipping in, going downstairs and doing whatever. I think that’s part of that fantasy that a lot of gay life has removed the necessity for but not the desire for. There was something about all that structure I find really appealing. I don’t mean that in a fascist way, at all, but there’s something about that decision to do something and stick with it. The sex club images were about: what is the meaning of that space when there aren’t people there doing what they’re famous for doing when they’re there? Each of those clubs had a whole different scenario… One of the clubs I photographed was a three story club in a bank vault right near the Élysée Palace. I thought: there’s something about the underground that’s interesting, that has its own little hive of activity. It’s sort of like doing a portrait of someone I don’t really know. They’re ominous. They’re supposed to be. They’re not supposed to look like a funfair.

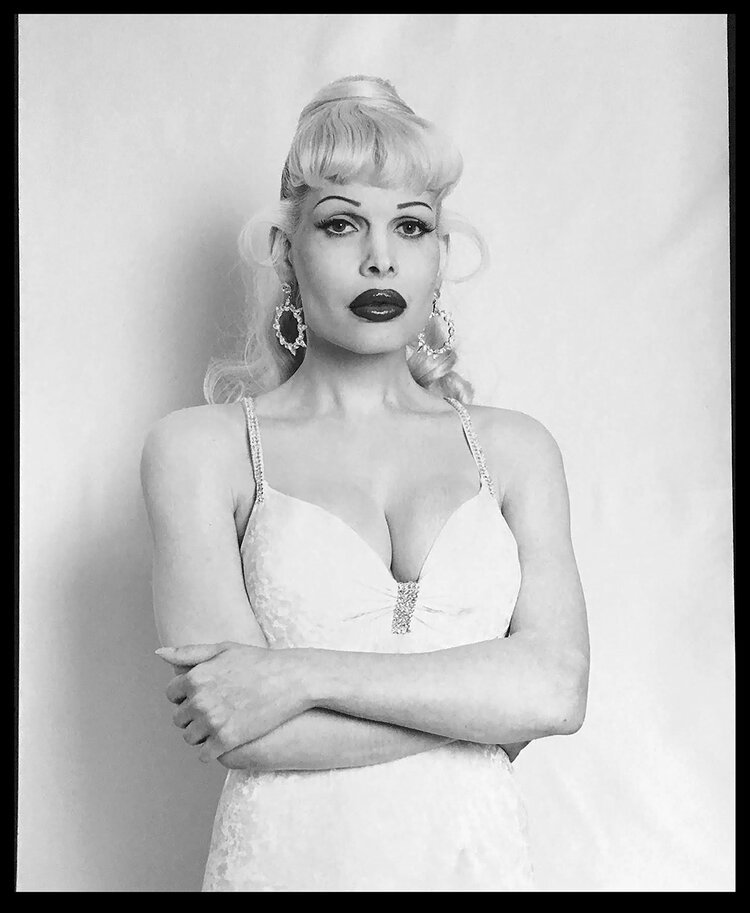

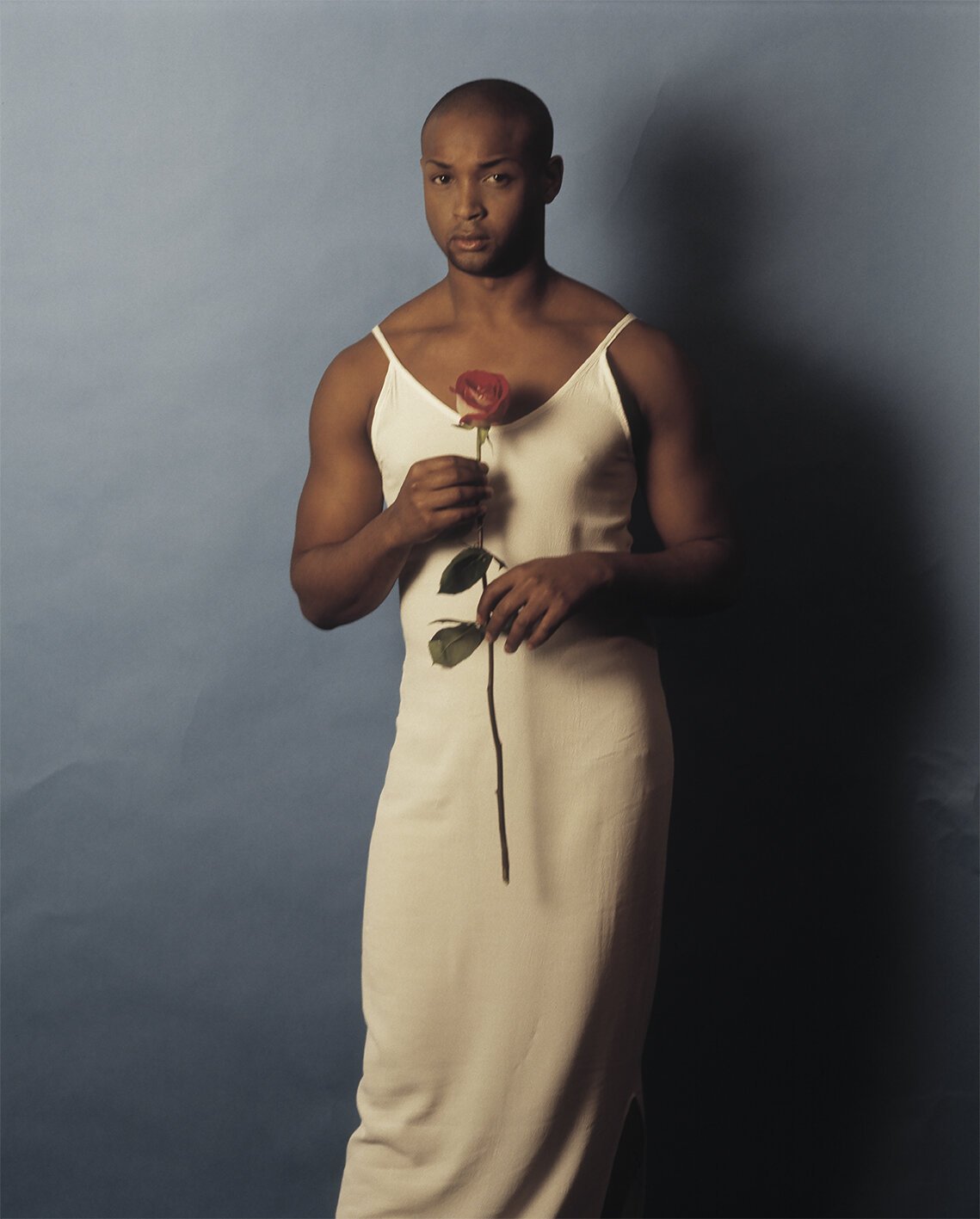

“OUR LADY OF THE FLOWERS” (AFTER GENET), ANDREW SHOALS, NYC N.D.

You live in the South now. Are you interested in photographing Southern subjects like the ones Walker Evans documented?

I am, but I’m not necessarily interested those Southern subjects. A lot of people are doing it. When I came down, I thought about it a lot. And I do think there are stories here that still can be told, but I don’t want to tell them. I’m not going to drive out somewhere and photograph someone. It’s not what I do. I don’t know how you extricate people in that world. I photographed some of the Legendary Children. I photographed Brigitte Bidet [dancer Joshua Rackliffe] both in and out of drag. I see all the people that are doing Southern subjects, and I think it’s amazing. It’s not my thing. I do think there’s subject matter here--I really do--but it’s not my thing.

Michael James O’Brien is one of the curators (alongside Emily M. Getsay and Le’Andra LeSeur) of WUSSY’s upcoming ‘High Visibility’ exhibition of queer Atlanta photographers—presented with Atlanta Photography Group and Atlanta Pride.

Don’t miss the ‘High Visibility’ exhibition premiering on October 9th at 7pm EST with an Artist and Curator talkback. There will also be two Artist Talks in the following weeks — ‘Performance in Photography’ on Thursday October 15th at 7:30pm EST and ‘Unraveling the Gaze’ on Thur, Oct 22nd at 7:30pm EST.

Register and RSVP for all those events by clicking here.

—

Andrew Alexander is an Atlanta-based writer and critic. His work appears regularly in Burnaway, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and other publications. He loves art, travel, bourbon and old records.

Archive

- February 2025

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- October 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- June 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015