Queer Film Classics: Gregg Araki's Teen Apocolypse Trilogy

THE DOOM GENERATION, 1995

The 90’s were a clusterfuck. Generation X juxtaposed between commercialized individuality, guzzling cappuccinos like fascist Italy in combat boots underneath Gap ads and Nike signs. The cultural phenom of Prozac Nation romanticized bipolar babes while the robust Glamazon Supermodel of George Michael videos were replaced with "heroin chic" waifs. Kurt Cobain’s suicide note noted that being "too sensitive" was a curse. The grunge era cultural martyr of the 27 Club, misinterpretations marketed to the masses in his wake, followed by yuppies blaring Matchbox 20 and Goo Goo Dolls from car stereos in shopping mall parking lots.

1995, being the year that Creed formed, marked the downfall of "grunge", and goth counterculture resurged with industrial-influenced bands like My Life with the Thrill Kill Kult and glam hybrid Marilyn Manson. "Alternative" Pavement and Weezer moved from college radio to MTV, causing V-neck sweater shortages at thrift stores. Britpop rode the peacoat-tails of shoegaze, Liam Gallagher-Beatles-bitch humming Ride's "Vapour Trail". Meanwhile techno downed ecstasy with glow sticks and candy necklaces, props to its cooler cousin trip-hop and the magic that was Bjork. These genres would eventually find themselves rehashed by Tumblr "sea punks".

"Growing up too fast" was the prominent teen film theme from the 1950's juvenile delinquent and the graphic '90s version a la Larry Clark and Harmony Korine’s appropriately titled Kids smeared as “child pornography”. Combined with frequent nihilistic rantings and a disdain for “society”, though not bothering to act like the hippies parents before, 90’s youth easily adapted to a “life sucks then you die” stance, which is perhaps the basis of Gregg Araki’s "Teen Apocalypse Trilogy".

TOTALLY FUCKED UP, 1993

Totally Fucked Up (1993), Doom Generation (1995) and Nowhere (1997) all center around hunky James Duval whose acting career began by playing "this teenager who drinks Drano and kills himself… a dream come true". Not widely released, the indie circuit’s "rag-tag story of the fag-and-dyke teen underground, a cross between avant-garde experimental cinema and a queer John Hughes flick" explored the sincere but scathed hopeless romanticism of those who half hold hope yet attempt squash love anytime disappointment comes around.

Araki’s insistence that queer characters stay in the periphery (if not the focus) started with The Living End, an HIV-positive "gay Thelma and Louise" dissed as "pornographic shit" by an LA video dubbing company. The Living End was stronger and more symbolic in its apocalyptic absurdism than Totally Fucked Up, more similar to Doom Generation, but each Apocalypse film emphasized the diatribe of relationships and struggles of a larger group than the isolated singular self destructive relationship in Araki’s debut.

Totally Fucked Up was partly filmed on camcorder pre-Blair Witch, commenting on queerness in the transient haze between childhood and adult life. "Being gay in the ’90s is not just a matter of what you do when you have sex. It has to do with a whole outlook, your place in society, your feelings toward government, politics, culture. Because homophobia is so prevalent, it becomes ingrained in your personality on all levels,” Araki states. “I am in no way a spokesman for gay people, but being gay in a society like this totally affects my films. Being queer does put you outside or underground."

TOTALLY FUCKED UP, 1993

Relying on youth culture, promiscuous relations, low budget tricks and bold titled shots, it was clear Araki was highly influenced by Godard. Glimpses of characters’ psyches flash by UFO-style, dissolving into darkness, Araki’s disillusioned teen and their inner world an adventure in itself. Similar to Godard’s work, capitalistic entities overshadow settings where emotions erupt, showcased within the plastic commodity society has become. Regardless of the varied race, gender or class, TFU comments on what it is to be a queer on-the-edge ‘90s teenager with indirect but powerful philosophical statements about the imbalance between microcosm and macrocosm.

Araki expanded on Godard’s influence: "I originally wanted to do Totally Fucked Up as my sort of Masculin-Feminin, exploring the issues faced by gay/lesbian teenagers in a pretty hostile socio cultural climate (the days of the AIDS epidemic, homophobic a-holes like Lyndon Larouche, etc). Working and hanging out with a cast of nonprofessional actors who were all around 18-19 at the time inspired me to write the next two films, focusing on that subjective state of mind of being a teenager, having no idea what your future might hold, experiencing life as one big question mark.”

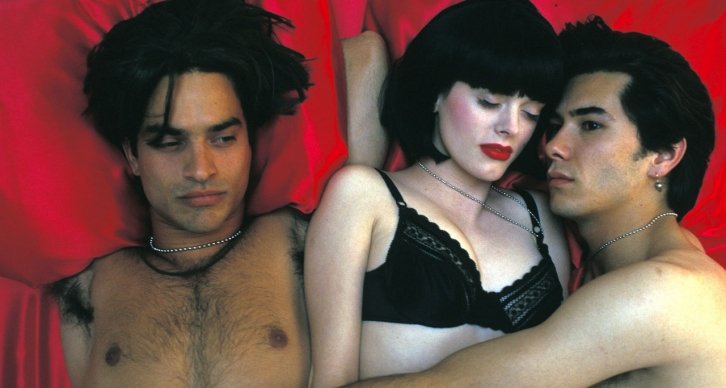

It was the cartoonish teen angst of The Doom Generation that gained Araki solidified popularity. Like The Living End’s fugitive road trip, an accidental string of slayings in bars, gas stations and drive-thrus confines three teens to motel rooms and abandoned warehouses with a script full of hilarious one-liners reflecting Teen Loserville’s twisted nature. James Duval is the gullible Jordan White, puppy-eyed for girlfriend Amy Blue (Rose McGowan) whose plethora of creative insults in “valley speak” and Anna Karina French New Wave fashion attracts a nihilistic third, Xavier Red (Johnathon Schaech), the antagonist whose arrival sets off a streak of freak accidents and bad luck.

THE DOOM GENERATION, 1995

This dark comedy binges on bizarre violence, but the story always reels back to the intense sexual tension between the triad. Doom Generation was the most accessible softcore ‘90s teens could access AND relate to. The sex scenes executed between Amy Blue and either Jordan or Xavier features close-up focus of their faces during orgasm, a signifier of Araki’s cinematic intimacy, and is touted as Araki’s "first heterosexual movie". Xavier Red confronts both Amy Blue's commitment to Jordan White while challenging the cracks in Jordan's seemingly straight facade. If Totally Fucked Up is Araki's Masculin Feminin then Doom Generation is Araki's Weekend.

Opening with Nine Inch Nails, perfect for pent-up bisexual boys with greasy hair, stupid tattoos, and black denim, the film’s softer scenes are sprinkled with shoegaze. Cocteau Twins and Slowdive are used in nearly every Araki film, his soundtracks a tool of emotive inflection. The end is tragic, cringe-worthy, trigger-intense, involving homophobic rednecks, setting a comparison to the consensual and safe exploration of the characters’ sexuality against an oppressive society that thrives off oppression and power.

Aptly described by David Moats in The Quietus: "To this day, The Doom Generation still seems to divide critics. For fans of B-movies and horror, it was a bit too pretentious and arty. For others it was a failed art film, too loose and shambolic to achieve its goals. For cineastes who prize things like 'plot points' and 'character development', it simply didn't compute. But for fans of similarly perverse mixes of high and low culture, and reckless genre mashups, it's an absolute masterpiece. Once you realise it's a movie about being a teen, it all makes perfect sense. For a hormonally charged adolescent, there's no middle ground: everything is either eye-wateringly boring or a matter of life and death. Everyone is against you and out to get you and no one understands."

NOWHERE, 1997

Doom Generation's set designs were more robust than Araki’s previous and would serve as a precursor for the highly-stylized and final installation in the "Teen Apocalypse Trilogy", Nowhere. Raver culture takes over and Araki’s allegiance to his home base Los Angeles created the perfect bubble for kids to fuck and get fucked up morning, noon and night. Unlike the first two films, the enormous cast of characters in Nowhere creates an overwhelming amount of side plots yet somehow manages to flow as different characters and stories intertwine.

Nowhere is also outrageously 90s celeb filled: Ryan Philippe shoves a chocolate heart in Heather Graham's pussy eating her out in a convertible, Baywatch's Jaason Simmons is a TV heartthrob who brutally rapes the young idealistic Egg, many characters visit dominatrix duo Debi Mazar and Chiara Mastroianni, and John Ritter plays a crazed televangelist condemning and converting the "hopeless". Amongst dozens whose cultures vary between music, sexual kinks, drugs, eating disorders and political affiliation, Dark Smith (James Duvall) experiences disruptive visions of a reptilian with a ray gun, initially seen zapping away three valley girls (Shannen Doherty, Traci Lords and Rose McGowan).

Nowhere is ominous and Dark Smith's hallucinations foreshadows the apocalyptic mystery ahead, the only character aware of the horror that awaits while everyone remains obliviously nestled in their drama and drugs. Dark’s visions of a sweeter kind, an esoteric connection to a dreamy boy that leaves him longing for a gentle (and monogamous) relationship, against being one of many partners with his polyamorous main, Mel (Rachel True), is another conflict. Mel was the first character I recall expressing ideas about the emotional responsibility involved within polyamory, dividing her time between Dark and the grape-haired proto riot grrrl Lucifer (Kathleen Robertson).

NOWHERE, 1997

While the aspect of craving monogamy exists in all three Araki "Teen Apocalypse" films, the director does not diss those that want poly relationships. Araki portrays intimacy equally both in the heat of hookups and the intensity of love but tends to judge neither party and shows how characters react and grow from these situations. Even though these movies are filled with comical interjections, cynical attitudes disassociating themselves from horrific or grotesque situations, Araki's films remain integral gems to "New Queer cinema".

20 year from the release of Nowhere, The Teen Apocalypse Trilogy is a 90s tome of queer youth culture ahead of its time. Can't Hardly Wait on ecstasy with alien takeover waiting in the wings, Nowhere was Araki’s strongest film to date at the time. With a knack for the coolest and most colorful B-movies focused on goofball teens immersed in corrupting counterculture, as a queer director with queer characters, Araki predicted not only fashion and drug use to come, but the sexual fluidity and gender expression we are familiar with today.

"Bisexual sounds to me like an old school scientific kind of category. I have always believed that sexuality is not really black and white, that it is a gray area. As time goes on, people become more open and fluid in terms of their views of sexuality,” Araki states. “The younger generation, their view is not really about labels and categories and declaring themselves. It is very unusual for an American movie to not have consequences because of the sex. As a middle aged adult, those experiences I had in college those made me who I am today. The things I learned about myself I still use to interact with people. They are an important part as your evolution as a person. I don’t think of them as titillating or even erotic. I find them fascinating."

Head over to our Spotify for some 90’s playlists and take our fun Buzzfeed 90s Queer Youth quiz

Archive

- February 2025

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- October 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- June 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015