Indigenous Renaissance: Revitalization by Young Native Americans

COURTESY OF @TONECROWE ON INSTAGRAM

“Chloé, meet Antone,” we shake hands and his grip is warm, “This is my new friend Chloé.” I was pleased to meet the boy I’d been seeing around classes, talking to everyone and laughing a lot. I loved his dark hair and rounded, prominent nose that stuck out of his face in an elegant triangular slope. We spent the rest of the day as friends in between classes, and I learned that Antone Crowe came in a set of four brothers, The Crowe Brothers, a band of brothers inextricably legend to my home town, as musicians and artists.

courtesy of @tonecrowe on Instagram

At the end of the school day, a crisp and gentle September afternoon, I went home with my Nana, telling her of my ninth-grade adventures. When I mentioned the Crowe Brothers she seemed more interested, “Is he an Indian?” I didn’t know, or ever think to ask. I never met other Indians outside of my family.

I would come to find out that the Crowe Brothers were part of the Brothertown Indian Nation, a tribe composed of multiple resettled east coast Algonquin tribes, residing along Lake Winnebago in Wisconsin. It would bubble up eventually, as my nana reminisced about her childhood, that Anna Crowe, a matriarch with a lyrical name, babysat my mother and uncle with her own brood. One of her sons, John, is Antone Crowe’s father. Pouring over an image of a group of black and white sullen Indians, telling stories of the people she knew and how they related to our family and the Crowes.

I listen when my Nana and her siblings talk about the old days, growing up Indian. I long for the pieces that I have been slowly arranging of myself and those before me. But often I fall victim, as many young natives of my generation, to feeling invisible. Racism by systematic erasure of Natives in education, pop culture and news has a negative influence on the societal view of Native rights, but on how Natives view themselves as well.

“Pressure to feel like you’re Native enough can be destructive and hinder people to move forward. Even when they have the agency to do so.”

A 2018 study by Reclaiming Native Truth, explored a host of institutional, social and historical influences on modern Native culture, representation and identity. Focused primarily on building new narratives for indigenous people, the research indicates glaring negative effects from this invisibility. Sample respondents who had little education and awareness of Native plights, were less willing to support the range of social justice issues from treaty rights to eradicating racist mascots. One participant articulated that, “I feel like Native Americans do not experience a great deal of discrimination mainly because I don’t hear about it in the news.” This lack of representation in media and culture reinforces the stigma that Native Americans are a “thing of the past.”

Ironically, my family’s tribe, The Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation, survived forced land removal, assimilation, brutalization, and attempted genocide, like most tribes, only to be portrayed as if they do not exist. In museums, Indigenous people are represented as they lived in centuries past, enforcing the erasure of our contemporary reality. Activist Somah Haaland, whose mother is congresswoman Deb Haaland, one of the first Native American women in congress, reports that, “In history books, at historical sites, and in museums, Native people are often framed as a people who participated in the making of America but who no longer exist in modern American society.” Since educational media is often aimed at children, this is generally dangerous — but especially when the child is Native. This presents Native identity as something that has come and gone. A retched pill I swallowed as a young girl.

Yet, I am kicking out against external and internal elimination. My friendship with Crowe, the death of my great Grandmother and fluent Potawatomi speaker Che-Quess, and the constant struggle for my identity inspire me to do more and to do it for everyone, not just myself. This sense of purpose and reclamation is surging in younger generations of Native Americans. Many are using art and technology to learn fading tribal languages, continue traditional media like story-telling and enforcing self-care.

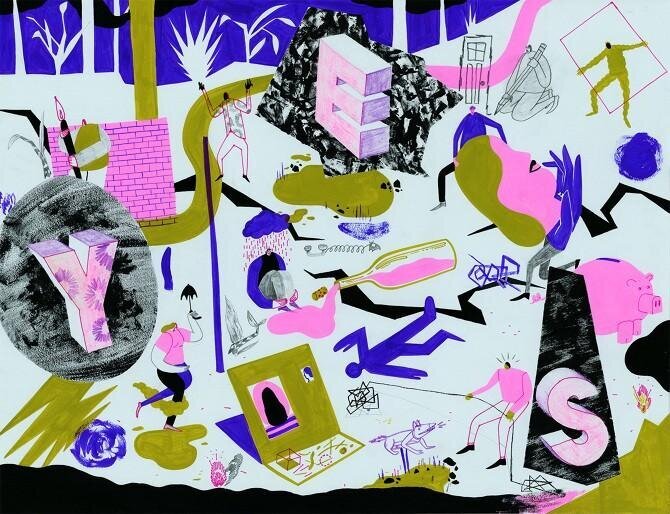

D O I T BY EDDIE PERROTE, FROM CROWD PAINTINGS, 2014

My cousin Christine Trudeau rerouted her pursuit of the arts towards journalism when she became aware of the great disparity in Indigenous reporting. This “void of coverage” as she puts it, gave her the confidence to manage her learning disability, breakdown the limitations she had placed on herself and confront the privilege that kept her from feeling “native enough.”

“There needs to be someone in the room,” she tells me, as if she is speaking straight to my own insecurity, “Even if it is not someone who is ready.” Trudeau, who is on the Native American Journalist Association’s Board of Directors, uses her educational background to advocate and cover her community, whether she was raised on the reservation or not. “Pressure to feel like you’re Native enough can be destructive and hinder people to move forward,” she advises, “Even when they have the agency to do so.”

“This is somewhat of a cultural renaissance brewing in millennial Native Americans that passes through generations, evident through the arts and through changing social norms.”

As I look up to Trudeau as an elder cousin, I look up to another cousin, Eddie Perrote. Perrote is a freelance illustrator and graphic designer. He believes, like Crowe and Trudeau, that today’s Native youth have a responsibility to “be safe, healthy, and not let trauma and racism continue to damage our communities.” This self-care is a direct reaction to the prevalent feelings of invisibility. Trudeau suggests “reviving yourself” through movement, the outdoors and holding yourself accountable. Crowe stressed taking care of nature as a means of this self-care.

As artists of story-telling, which is deeply rooted in Native culture, Crowe, Perrote and Trudeau are part of the younger Indian Country using relatively new-found accessibility to create and represent. A Choctaw artist, D.G. Smalling is using his voice in the same vein, drawing the parallels of growing inspiration, acknowledging that “Older people who had the misfortune of being conditioned not to celebrate or speak are returning to the culture.”

Smalling continues, “This is somewhat of a cultural renaissance brewing in millennial Native Americans that passes through generations, evident through the arts and through changing social norms.”

The self and societal expunging that goes along with lack of representation stands to battle the liberating and young Indian Country. Toeing the line between representing Native identity without defining oneself with it, we resilient and existent people are still here.

—

Chloé Allyn is a poet and visual artist living in Atlanta. She works in many disciplines but specializes in pleasure and words.

Archive

- May 2025

- February 2025

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- October 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- June 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015