Hope in the Indigenous Renaissance

Don’t miss Part One of this article written by Chloé Allyn — click here!

I return to the petite booth at Round K with two cups of coffee, one for my cousin Eddie Perrote, “Because I was so late,” I say. He smiles, like my grandmother does, and I slide into the wooden booth across from him. Nervously, with the thrill and embarrassment of meeting a family member for the first time — both of us into our middle 20s — I pull questions from my rehearsed list.

“To me, you look really native. You look a lot like your dad [My great uncle John.] Do you think other people see that? Do you ever experience anything negative about the way you look?”

Perrote, who is a freelance artist and designer relies on himself for finding work, “A lot of the time, I don’t see people face to face. But when I do, I don’t experience anything.” He continues with familiar eyes behind thick black glasses, “People don’t know what natives look like.”

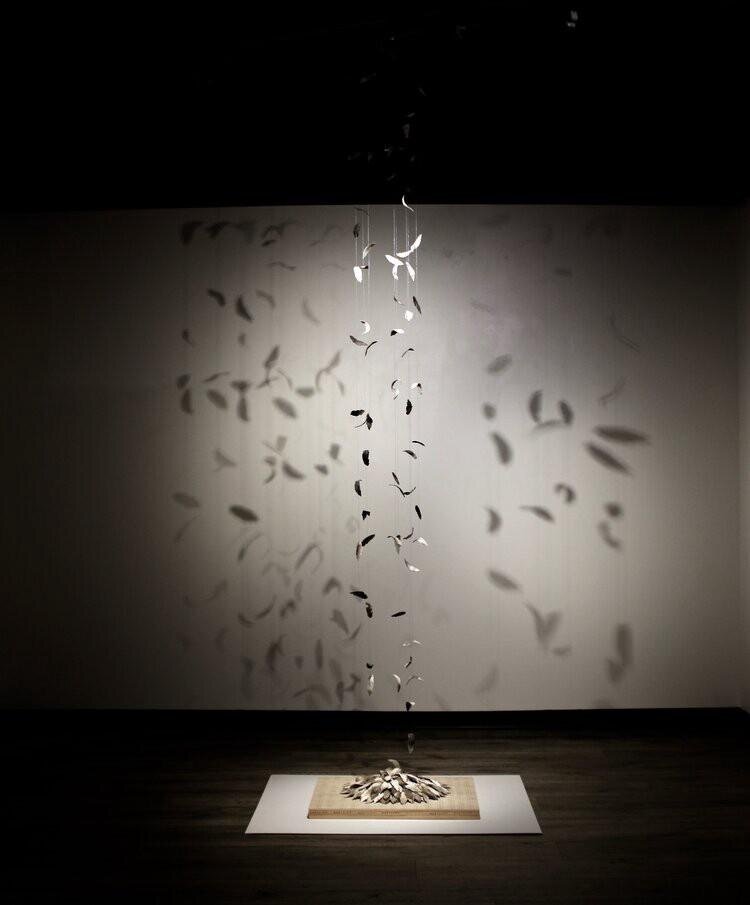

ROYALTY BY EDDIE PERROTE, COURTESY OF PAPERDARTS.COM

Unfortunately, what many Americans think they know about Indigenous people is rooted in half-truths, microaggressions or a belief that the peoples are a thing of the past. This perspective is damaging for the identities of living Natives but also for the commonwealth of Indigenous people in modern society. Researchers have found that this lack of visibility decreased social awareness for Native rights. It is clear that conversation would benefit if there were more representations of living Natives using existing talents in our contemporary world.

Recent attention in media like the Dakota Access Pipeline protests, two elected Native congresswomen and Senator Elizabeth Warren’s defunct claim to significant Native heritage, has brought some of the Native plight to public attention. Though there is still a gap between negative coverage and positive representation. The fight for representation, equality, and recovery is long from over, so living Natives are using artistic talents to heal the contemporary Native image.

My cousin Brigetta Miller, a member of the Mohican Nation and an associate professor of music education and ethnic studies at Lawrence University, is passionate about using education to revitalize and heal the Indigenous narrative. During the 2020 spring quarter at the Wisconsin based liberal arts college, she instructed two courses that survey the effects of colonization on contemporary Native culture. Of the courses, one titled “Decolonization, Activism and Hope: Changing the Way We See Native America,” Miller aims to honor and perpetuate Native voices in the material, voices that are often not represented in institutional education.

MURAL AT LAWRENCE UNIVERSITY, CELEBRATING A COLLABORATION WITH MITIKA WILBUR, COURTESY OF BRIGETTA MILLER AND LAWRENCE UNIVERSITY

“The whole goal is for students to better understand colonization throughout history and identify its effects on all of us even today — systematic structures are still in place in higher education, media, literature,” says Miller, who is my educational inspiration. “I strongly believe knowledge is power and healing can only begin if we clearly understand our past, reclaim who we are, and move together toward reconciliation and creative solutions.”

Hitting the renaissance nail on the head, she concludes, “It’s an exciting time right now because we see many Native youth expressing their culture and identity in new ways. This generation is bold, bright, and beautiful!”

This bold beauty is especially true for Native artists, many of which are using their talents for exploration of identity, activism and continuation of tradition. Perrote, whose works are both bright and bold, thinks of his works as a continuation of tradition.

“Although my work doesn’t overtly cover topics relating to our traditions,” He tells me, “I feel that the content that I enjoy working with, my approach, and continuing to celebrate artistic expression and its role in our lives as storytelling, is in itself inherently linked to our culture.” Perrote, like many artists, is a living example of Native America, if not an activist in literal pursuit of justice. This representation is just as important.

Other artists and writers, though, have found a strong foothold in using identity in their work to shed light on Native rights issues. The U.S. Department of Justice found that Indigenous American women face murder rates that are more than 10 times the national average, and that homicide is the third leading cause of death for Native women ages 10–25. The legacy rooted in violence against both women and Natives predates the founding of the United States, and continues today.

Artists like Valaria Tatera have tapped into the coalition for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, finding a source of inspiration and a route to healing through activism. After witnessing Native youth rising up and learning of her own thoroughly Native family history late in life, Tatera, a Wisconsin-based Anishinaabe artist, came out professionally as Indigenous, taking up her own fight. As a member of the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, Tatera combats the erasing effects of colonization with deliberate self-identification, a powerful motivator in a world of self-effacing Natives.

PRINCESS TWO FEATHERS BY VALARIA TATERA, COURTESY OF VALARIATATERA.COM

On the phone, Tatera’s voice is warm in my ear. Our initial meeting brings tears to my eyes, forming a connection of understanding between us as Natives and artists, over identity. It is freeing to not have to preface the conversation with a brief explanation of historical trauma, colonization and Blood Quantum — three of the greatest evils faced by contemporary Indian Country.

“Historical trauma doesn’t define me,” she tells me, “I’m not a victim and I’m taking the healing forward.” Tatera’s most recent exhibition, Good to the Last Drop, featured at Edgewood College in Madison, Wis., investigates the intersections of ethnicity, gender, suicide, missing indigenous women, commerce, and water quality. She reinforces, during our conversation, that she leaves space in the work for healing. Allowing herself to go forward in a positive way.

As I trust her voice over the phone and rely on the comfort of our camaraderie, I can see the truth when she tells me that she aims in “taking back the matriarchy.” A traditional societal value of some tribal governing. I am comforted by the wisdom of her female middle age, knowing that there is so much between us that runs understood from womanhood, art and Native identity.

MY MOTHER’S BEADS BY VALARIA TATERA, COURTESY OF VALARIATATERA.COM

As important as expression, activism and connection between members of Indian Country can be, mental and spiritual healing are the foundational steps to staying strong and reviving Native traditions. In a recent study published by The Permanente Journal for the U.S. National Library of Medicine, it was found that Native American and Alaskan people “experience more traumatic events and are at higher risk for developing post-traumatic stress disorder compared with the general population.” This trauma is not only physical, but mental, and the issues compound, with a host of complications like discrimination, poverty and lack of access to medical treatment.

An interviewed Native Healer from the study suggests that historical spiritual medicine can be a particularly Native approach for contemporary Natives to not only reconnect with their health but with their heritage. “Native people are very spiritual … [some] don’t know that about themselves and [have] never been part of … their culture … never had guidance from elders.”

For Perrote, Tatera and Miller, this concept of mental health and healing are at the top of the list. When asked for advice to contemporary Natives, especially younger people grappling with identity, taking care of mental health came first.

“I feel that the responsibility of younger indigenous people is to maintain a healthy life and work to not let the systematic oppression, racism and generational trauma continue to damage our communities,” explains Perrote, and with an especially poignant and inter-generational reminder to, “Be healthy, be safe, and strive for a heart filled with love and kindness for your families, friends and ancestors.” Looking at Perrote’s artwork and hearing his wisdom on our first meeting fills me with love for art, family and my culture.

EDDIE PERROTE COURTESY OF BIBELOTMAGAZINE.COM

Another artist and expecting mother, Geneva Torres, who is Chiricahua Apache, Lakota and Mexican, explains her sense of duty as part of the younger generation of Natives who have the freedom of expression of identity. “I didn’t find out that I was Native until I was 15 years old. I got the sense from my elders that being indigenous wasn’t something to be proud of.”

This effect is widely imparted by the late 19th and early 20th treatment of Natives with relocation, forced assimilation, sterilization and dehumanization. “I feel the duty to show my pride in being who I am and learning as much as I can about my heritage. This task takes on generations of suffering, racism, and oppression but layers of Native beauty were still being added on as well.”

Torres hits on the sliver of beaded and deeply seeded hope that she, and I and many young Natives feel today; the inexplicable sense of age in our souls and history in our blood, in our hearts. We are still here, we look like ourselves and like our ancestors.

“My hope is for our generation to see our heritage comes from our land. My hope for my people is that we will move about like the wind once again.”

—

Chloé Allyn is a poet and visual artist living in Atlanta. She works in many disciplines but specializes in pleasure and words.

Archive

- February 2025

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- October 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- June 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015