A Case for Queer Christianity

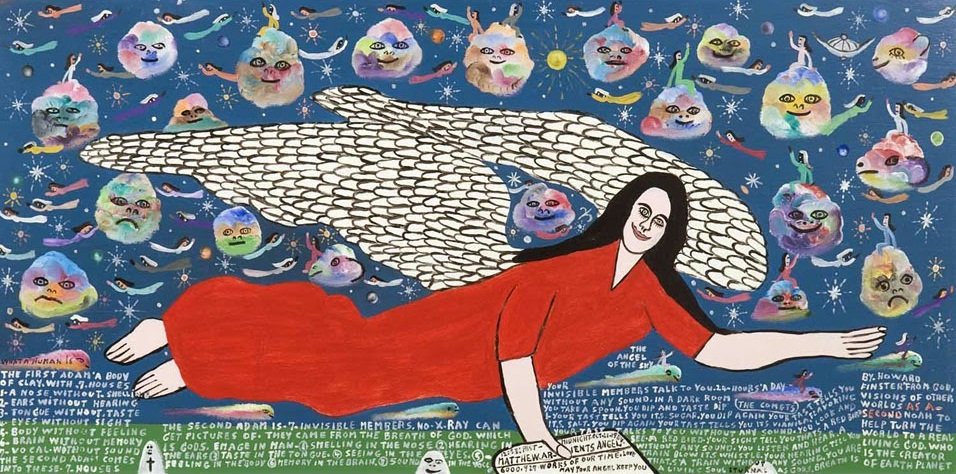

HOWARD FINSTER

“I came so that you may have life, and that you may have it more abundantly,” my mama says through the phone. I’ve heard her say this before, so many times, the center of her belief. “That’s what Jesus says. He did not come to judge you, but so that you may have life. I don’t know what God’s plan is for you. But I know he wants you to be happy and whole.”

“And think of the people Jesus hung out with,” my dad comments from the background. “He didn’t hang out with conservative or, you know, the upper crust. He hung out with taxpayers and prostitutes and—think about who he would choose to be near now, who would be in his company.”

I’m sitting on my back porch and crying with my beer between my legs. I have reached the end of a long, wounding conversation about going on testosterone. It’s such a beautiful day outside and there’s somebody in the courtyard below me smoking a cigarette and watching me alternately cry and laugh.

My parents are religious, not in the institutional way, but in a deeply personal way that spurns the Old Testament and holds tight to the Christ who promised love, forgiveness, and the richness of life. Both of my parents, like me, struggled with intense feelings of isolation, confusion, and hurt as they grew up. I think they thought raising my siblings and I with their own beliefs, rather than the beliefs of the Baptist or Catholic churches they came from, would give us safety. I came out to my parents as nonbinary and transgender last summer, and since then, they’ve struggled with reconciling their love and belief in me, and their love and belief in the Holy Spirit.

My mama speaks in tongues when she prays over me. My dad has the power of prophecy. My mama has the power of words, which means God can tell her what to say. She calls me and my siblings their inheritors. She likens us to Jedi. She tells stories about looking in the mirror and laughing her ass off, she was so taken with the Holy Spirit. My older siblings tell me stories about bible study meetings with my mama repeating “fish” ecstatically and another woman waving her arms like wings as she deeply breathed. I never realized until a year or so ago how religious my family was, because I didn’t realize others were different. I think if my parents had the vocabulary, they would realize how close to queer they are, in their interactions with the world and with each other. Maybe that is only wishful thinking on my part, though. Maybe it’s because my parents’ and my religions are so close together, that I keep pushing for a middle ground. Meanwhile, they try to convince me to reach all the way to them. I bait them with pieces of poundcake; my grandma's recipe. Comfort food snags the cautious fish.

“Jesus said, I came so that you may have life, and may have it more abundantly.” I think of drag queens, house shows, sex in bar bathrooms, and living off of Diet Coke and cigarettes. As for me and my House, we will serve the Lord. I know this isn’t quite what Mom means, but I know they’re adjacent. So right now my parents and I are looking at each other across a river and asking, “Why is this so hard for you? I genuinely don’t understand.” Both of us are breathing beer and blood in our attempts to be nearer to the core of life. You both know how sad I was for eight years. You both know I prayed to become an angel, long before I knew how to fathom suicide. Why won’t you just be glad that I am finally ready to be a human? I don’t understand. I don’t want to hurt you, but I don’t understand.

My first steps towards re-realizing I was queer was when I told my mom I didn’t want to wear dresses, florals, or bright colors anymore. I came home from college and I piled on the bed all my old clothes that I wanted to get rid of. There were deep purples, pinks, lace, bohemian shawls, flowing pants with pleats at the waist. It had been the standard--I was an artsy gal, after all. But suddenly I found them repugnant, like foreign tissue my body had rejected. I wanted for them to be gone and to be clothed in ambiguity, like a restless monk.

I was so used to my mom's understanding that I expected her to be excited for me, or at least ambivalent. Instead she seemed to feel something close to despair. She asked me if I wanted to wear black and grey and blue because I was depressed. She kept repeating that this was making her worried. In exasperation, I gestured to the rainbow sprawl on the bed. I said, “Look at this stuff. Do you really think this looks like me?”

“Yes,” she answered.

“Well's, that’s not the way I see myself.”

“Then change the way you see yourself.”

I have experience doing this. I had forgotten it: in seventh grade, after realizing I was queer, I came out to a friend in my small group. She told me that she still loved be, but that being gay was a sin, which, at the time, I had not heard yet. The Christ my parents had taught me about, and His father, could not possibly condemn two people loving each other. My friend pointed me towards Leviticus, and the verse that demonized us. I could not have known about the debate about the translation, or the ridiculous laws surrounding it that were so routinely ignored. I did not know Christ acted to spite the past. All I knew was the verse, and it was incomprehensible to me. Leviticus was my first real heartbreak. I always thought Christ and God were unconditionally loving, happy, accepting beings. Now, Their words looked at me and told me that if I did this, I would be cut off from Their ultimate love, and it would be my fault. How could I do that? Who would I be if I did?

I decided to perform conversion therapy on myself, to decide to be straight and cisgender, and put pain behind me. I decided I was strong enough and smart enough to make the decision that would make my life and religion straightforward and easy. Whenever I was attracted to a girl, I focused until my mind distorted her, described her body as swollen and pinched instead of curvy, equated her breasts and hips with ripening fruit and therefore with rot. I warped beauty into revulsion. I began wearing eyeliner and push-up bras. I tried out drawing shirtless guys with shaggy hair in my journals. I felt like I was grasping at straws. For eight years, I wanted to be dead. I could not figure out why--the Holy Spirit didn't save me. My small group didn't. Bible camp didn't. The thing that had saved my mom from her patriarchal upbringing or my granddad from alcoholism or my dad from loneliness didn’t come for me.

I found myself as a queer person, not when I rejected faith, but when when I realized I could choose to see myself as solidified God. God could be sexless. I could be neither male nor female, but clear, and I could dress and present myself that way, whatever way I wanted. I could name myself. I could cut off and stitch in. I could kiss whoever I wanted, and somehow, it didn’t matter. Jesus didn’t care. It's okay that I want to live.

Scars, drunkenness, fighting for happiness, the hollowing out of a home and a community, these are gifts to me and my life at this moment. They are my abundance. My parents queered their Christianity. My mom queered her religion when she realized Christ wanted her to be an equal leader in her household. My dad queered his Christianity by insisting life was something to be enjoyed, not suffered through. They queered their Christianity together when they realized that their Christ would not condemn people to eternal suffering just because they did not believe in Him--Christ knows good people. So I queer my Christianity, too. They raised me to do it. I define my religion. I define what is abundance, and what is starving. I say Christ wants me to use the tools I have to make my world divine, to make my light brighter. I say I know what those tools are. I ask them to trust me.

My parents see this and yet they don’t. They wonder if it is a symptom of a wound. Are they looking through a kaleidoscope? God is myself and the air around me. Existence and creation is just a floating clot of God playing make believe, and nothing is more abundant than playing hard, living hard, wearing out, being reborn, retiring and reminiscing. I do not try to outrun the world. I am a part of it. I am the world. It gives me peace and lets me sit with God as a puppy on my lap rather than a deadline on my journey. I think that Christ did not come for me to have eternal, unending life. I think Christ died so that I may have an eternal life, a singular and multiple life that experiences God constantly and is made of God and creates God every moment and therefore encompasses the universe. All religions are as real as I make them. My life is parallel with all that surrounds me. My journey will continue forever and when it ends so will everything else.

"The thief cometh not, but for to steal, and to kill, and to destroy: I am come that they might have life, and that they might have it more abundantly." -- John 10:10, King James Versio

Who, then, is the thief?

—

Penske McCormack is a writer and art historian living in Athens, Georgia, where they have been studying for the past three years. Their studies are focused on art conservation, art writing, and performance studies. In their own art, they experiment with movement as an intuitive form of meaning-making and communication, and use performance as a route to create, articulate, and experience genderless identity.

Archive

- February 2025

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- October 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- June 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015