Mourning Becomes Resistance: Hamed Sinno on Westerly Breath

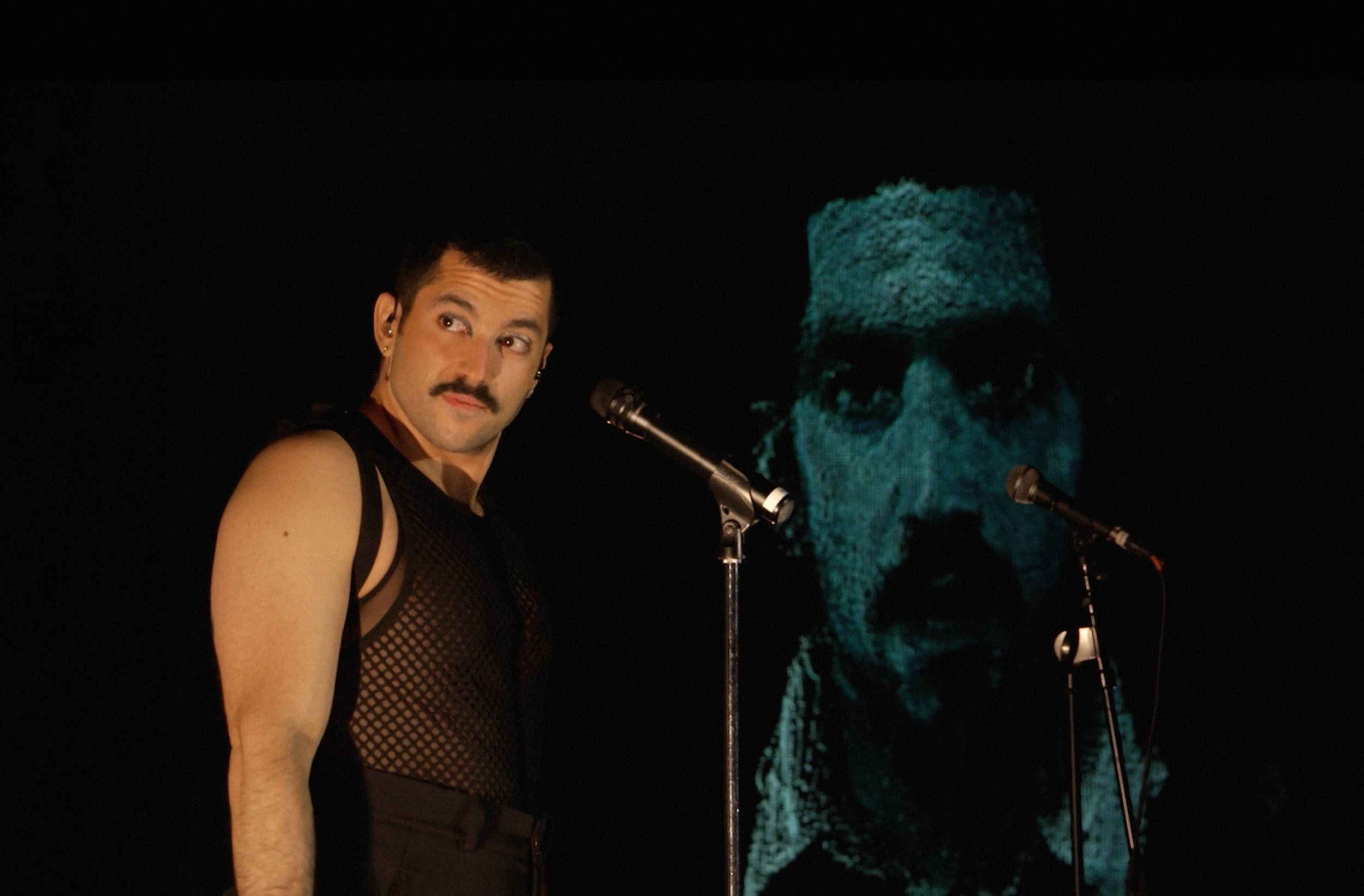

Hamed Sinno in Westerly Breath

This article was originally published in WUSSY Vol.13, available now in our online shop.

For Arab queer icon Hamed Sinno (once heralded as “the new face of Middle Eastern pop music” by Dazed Magazine) immigration to the United States from Beirut inaugurated a period of extended mourning—for their father who had died, for the explosion that had ravaged the city of their birth, and for the break-up of the celebrated band Mashrou’ Leila that they fronted for twelve years. For many exiles of the ‘Arab Spring’ generation like myself, the band had embodied the progressive political ideals that we had dreamed of, but tragically failed to realize. This “immigrant grief,” as Sinno described it when we spoke, was the subject of their stunning Westerly Breath, a site-specific opera performed by Sinno, their “cloned” voice, and a small string ensemble at the Temple of Dendur in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York for two evenings in late January 2024.

The symbolism of the Temple of Dendur couldn’t be more overdetermined: the syncretic Egypto-Roman temple had originally been erected soon after Cleopatra’s death in 31 CE, but was only disassembled in the 1960s ahead of the building of the High Dam, the crowning achievement of postcolonial Egypt’s putative technical prowess under President Nasser. Although Egyptian-American relations were fraught at the time due to the former’s alignment with the Soviet Union, Nasser gifted the temple to the United States (which Jackie O demurely accepted) as a recognition of the superpower’s assistance in saving twenty-two ancient monuments that would have otherwise been submerged under water with the construction of Lake Nasser, the largest man-made reservoir in the world at the time, behind the dam.

The setting, like the performance’s title, was a fecund metaphor for many of the ideas that Sinno was exploring. Westerly Breath didn't just invoke Sinno’s own journey to the “West” but also reminded audiences of their location in a museum that holds the exhumed human remains of Egypt’s indigenous people, ghoulishly encased in vitrines, for hordes of tourists to ogle at. It’s an acknowledgment too that in ancient (and in some cases contemporary) Egypt, the “West” was known as a place of mourning: corpses were buried on the Nile’s western shores, for it was regarded as cosmically appropriate that lives should end in the cardinal direction of the setting sun.

Sinno’s sung séance, which opens with an invocation of Atum, the Egyptian deity that masturbated and ejaculated creation into existence, quickly turns from the distant past to the most pressing political concerns of the present. It narrates, albeit in deliberately fragmentary form, stories of familial homophobia, the dream-turned-nightmare of Arab nationalism, the torture of lesbian communist Sarah Hegazi, who was detained after one of Mashrou’ Leila’s performances in Cairo by Egyptian state security for raising the rainbow flag in 2017 (ultimately taking her own life), and the question of Palestine, which couldn’t help but be at the forefront of every audience member’s mind when Westerly Breath debuted three months into the genocide.

Hamed Sinno by Stephanie Berger, Courtesy of the metropolitan museum of art

That the work premiered internationally on the 26th of January 2024, almost thirteen years to the day after the outbreak of the Egyptian revolution of 2011, seems particularly apt, as it contends with the dashed dreams of the generation of which Sinno has been said to give voice to as Mashrou’ Leila’s lead-singer and songwriter. But perhaps the true radical meaning of Westerly Breath lies less in its chosen subject matter but in the form that Sinno gives it. Throughout the work, Sinno duplicated their voice using an AI software called Descript, and fed it the text of the libretto. The cloned voice was then played on tiny Bluetooth speakers that Sinno held inside their cheeks and manipulated live. In doing so, Sinno quite literally put the words of others into their own mouth. This searingly original form contended not just with the psychic burden of being a medium through which the specters of the past speak, but also with being a ventriloquist that putatively “represents” the hopes and dreams of collectives like the “Arab Spring” generation, and in doing so inevitably (and sometimes even generatively) distorts them.

Hamed and I met for the first time over a decade ago on a barge in London, at a lunch hosted by French fashion polymath Michelle Lamy and the Egyptian photographer Youssef Nabil. We didn’t speak for over ten years, but re-met in early October after we both arrived in New York at an Arthur Russell tribute concert by the AIDS memorial in Greenwich Village, as appropriate a site as any for two exiled Arab queers to speak about their struggles and make sense of the shattered dreams that had once brought them together. Hamed told me they were working on an opera about death and the desecration of Egyptian monuments. I was writing a book about the very same topics from the perspective of the City of the Dead, the Cairene cemetery where my mother was buried and which was in the process of being destroyed by President Sisi’s military stooges, who were razing the medieval monuments to build highways.*

Hamed Sinno by Stephanie Berger, Courtesy of the metropolitan museum of art

Hussein Omar: Can you tell me the story of how Westerly Breath was commissioned? What was the story you originally wanted to tell with it?

Hamed Sinno: Mashrou’ Leila had worked on [British multidisciplinary artist] Oliver Beer’s commission at the Museum and through it met the curator for the Live Arts department. It was at Met Breuer and they were given the option of doing the main hall or the Temple of Dendur. I ended up at dinner with the curator and she asked me to pitch something when I described the research I was doing on speech synthesis at Dartmouth. So I pitched a solo project for the Temple, which I wanted to tell as a story of immigration.

I hadn’t looked into the Osiris thing, I hadn’t looked at the question of fractals.

Omar: What is the question of fractals?

Sinno: The idea is that I'm looking at these narrative patterns that play out inside one larger narrative. So there's a psychic fracturing of sorts, but each of those pieces tells the story of another fracturing. Everything is taken apart in order to be put together again. Osiris is ripped up into pieces and is restitched together again but becomes the first mummy and the god of the underworld. The temple is ripped up to be moved, and stops existing in the landscape as a temple. It becomes a different kind of monument.

With speech synthesis, the algorithm will take a vocal recording and break it apart into little phonemes and weave them together again. “The voice as seat of subjectivity” and the site of agency becomes obliterated by speech synthesis, and it becomes severed from the moment of its corporeal inception.

It can be a mummy or a weird kind of necromancy depending on who is moving the machine. The distinction being that, with a mummy, the dead subject continues to have agency, but with necromancy the dead are being animated by someone else.

Omar: And then of course October 7th happens…we re-met just before October 7th and the conversation that you and I had about the opera was very much about this idea of the fractal, or what needs to be pulled apart in order to come back together again. But the final version of the opera tackles questions that much more explicitly center around Palestine. You wear a keffiyeh in the final sequence, and you contend with not just how the people of Palestine were and are being exterminated but also how we all are, here in the United States, participants in the continued and continuous displacement of the native population.

Sinno: Most of this was workshopped in LA in December 2022 at the Industry [an opera collective that has a lab for new music]. So it's hard to answer the question when you’re still in the thick of this very weird, very racially charged genocidal catastrophe. You can’t perform or write a piece about immigrant grief without it being filtered through the question of Palestine, but then again I can’t think about or do anything without thinking about Palestine.

In other words, any mention of Palestine in the script was actually from Facebook posts dating back to 2021. The piece had already been written before the onslaught of this most recent escalation of imperial horror, but since the 7th of October, it's become impossible for most of us to not have Palestine color every aspect of our lives, let alone color how we potentially receive a piece that tackles the question of queer Arab diasporization into the heart of empire, right? So most of the text was there except the Sarah Hegazi sequence.

Omar: What is the Sarah Hegazi sequence and when did it get in?

Sinno: I had written it into the text-score in the outline from the beginning. I wanted four stories written in pieces that would fill in the blanks for each other. I wrote four stories that I put into a spreadsheet and disassembled them. I couldn’t write it. It was very difficult to write. I kept putting it off for years. Everything else was done with six weeks to go, maybe even a month, and this part was blank. “What the fuck are we doing here with this part?” Instead I basically went through five years of Facebook posts, I fed them to my text-to-speech thing. I cloned my voice on cassette tapes that I used in the piece.

The Facebook posts were from August 2019 to August 2022. It started from me leaving Beirut and the explosion, Sarah’s death and becoming an immigrant in grief. My solution four weeks before curtain was to use my cloned voice and put it in my mouth to say all the things that I couldn’t really say. It was the improvised part of the show. There’s still no score for it. I wrote instructions for the instrumentalists re key changes etc. There was no score in front of them telling them what to play. They could pick fragments from other parts of the score and play them together without coordination. To make a monster, which is what I was doing with my mouth as well as for this one six-minute section.

hamed sinno in westerly breath

Omar: Looking back to the beginning of your career, was there any explicitly political content in the band’s early music or did it become more and more politicized as events in the Middle East evolved?

Sinno: No, it was political right from the beginning. Obwa was about car bombs, and Shim El Yasmine was the first song I wrote in my bedroom. It was our first demo. Raksit Leila as a surrealist exercise was arguably very political. I am going to speak in tongues and do this exercise in free association, and you might decide it was completely meaningless but in its bareness was very political. They were political with a capital P which is much less interesting than the way they evolved toward the end, such as Ibn El Leil, which was dealing with how I was consumed by grief and mourning, which are very politically charged practices and affects—they are parts of our lives and psyches. The part that is personal, the part that is public and the parts that cannot be either. It was something I landed on after my father’s death. It’s not one of those things where the personal is political… I don’t know what the fuck I am saying.

That last album [Ibn El Leil] did something that I had wanted to do from the beginning but only then landed on. [The song] Tayf tried to address the relationship between queerness and the law, and the way to find a writing style that could speak to both. It was really one of the highlights of my career to write that song. The Lebanese law that criminalizes homosexuality is law 534, which criminalizes sex against nature. It was written about this queer club called Ghost, but the Mayor of Beirut illegally raided the club in 2012, but because the people arrested were working class there were no consequences.

I wanted to refer to how hyper-industrialization informs the making of a new nature. I anthropomorphize it all—the neon lights become my tears, it starts raining bullets, the electric poles become my bone marrow, people fucking and moaning become protest chants… I was making a queer monster, which references Sylvia Plath’s Mushrooms (1959), which is obviously a feminist text, but the bridge between feminism and queer liberation is really important for my politics. It was just a really good writing moment for me. It felt like I was finally doing something with the text that was political but that I hadn’t managed to accomplish for quite some time.

Hamed sinno et un de ses frères (2018) by Alireza Shojaian (@alireza.shojaian)

Hussein AH Omar (@totemsandtaboos) is writing a five hundred year history of Egypt as told through the story of his family as told through the story of the cemetery they are buried in. He also writes about the history of anticolonial thought, sexuality and psychoanalysis. He organizes with Writers Against the War on Gaza (W.A.W.O.G.).

Hamed Sinno (@hamed.sinno) is a composer, writer, performer, and social justice advocate. Their research explores vocalities as sites of political negotiation. H writes, and lectures about popular culture as engaged practice. They have been the lyricist and front-person for Mashrou’ Leila since 2008, agitating conversations around representation, free speech, and sexual freedoms in the Middle East. H has a BFA from the Department of Architecture and Design at the American University of Beirut, and an MA in Digital Musics from Dartmouth College. Their debut full-length opera, Westerly Breath, was in development at The Industry Los Angeles, and opened at the New York Met Museum in January 2024. Their solo debut, Poems of Consumption, explores the overlaps of consumerism, mental illness, and environmental crisis. Poems of Consumption debuted at London’s Barbican Centre in July 2023.